After Dropping 275 Pounds, Jelly Roll Shares Surprising Insights About His Journey

For the past five years, Jelly Roll, born Jason DeFord, has undertaken one of the most remarkable transformations in modern celebrity…

I’m 35, my son Nick is eight, and this winter our entire neighborhood learned a very loud lesson about boundaries.

It started with snowmen.

Not one or two. An army.

Every day after school, Nick would burst through the door, cheeks pink, eyes bright.

“Who’s Winston?” I’d ask, even though I already knew.

“Today’s snowman,” he’d say, like it was obvious.

He’d throw his backpack down, fight with his boots, and wrestle his coat on crooked. Half the time his hat was covering one eye.

“I’m good,” he’d grumble when I tried to straighten it. “Snowmen don’t care what I look like.”

Our front yard became his workshop.

Same corner every day, near the driveway but clearly on our side. He’d roll the snow into lumpy spheres. Sticks for arms. Pebbles for eyes and buttons. And that ratty red scarf he insisted made them “official.”

He would step back, hands on his hips, and go, “Yeah. That’s a good guy.”

I loved watching him through the kitchen window. Eight years old, out there talking to his little snow people like they were coworkers.

What I didn’t love were the tire tracks.

Our neighbor, Mr. Streeter, has lived next door since before we moved in. Late 50s, gray hair, permanent scowl. The kind of guy who looks offended by sunshine.

He has this habit of cutting across the corner of our lawn when he pulls into his driveway. It shaves off maybe two seconds. I’d noticed the tracks for years.

I told myself to let it go.

Then, the first snowman died.

Nick came in one afternoon, quieter than usual. He plopped down on the entryway mat and started pulling his gloves off, snow falling in clumps.

“Mom,” he said, voice thin. “He did it again.”

My stomach sank. “Did what again?”

He sniffed, eyes red. “Mr. Streeter drove onto the lawn. He smashed Oliver. His head flew off.”

Tears spilled over his cheeks, and he wiped them with the back of his hand.

“He looked at him,” Nick whispered. “And then he did it anyway.”

I hugged him tight. His coat was icy cold against my chin.

“He didn’t even stop,” Nick said into my shoulder. “He just drove away.”

That night, I stood at the kitchen window, staring at the sad pile of snow and sticks.

Something in me hardened.

The next evening, when I heard Mr. Streeter’s car door close, I went outside.

“Hi, Mr. Streeter,” I called.

He turned, already annoyed. “Yeah?”

I pointed to the corner of our lawn. “My son builds snowmen there every day. Could you please stop driving over that part of the yard? It really upsets him.”

He looked, saw the wrecked snow, and rolled his eyes.

“It’s just snow,” he said. “Tell your kid not to build where cars go.”

“That’s not the street,” I said. “That’s our lawn.”

He shrugged. “Snow’s snow. It’ll melt.”

“It’s more about the effort,” I said. “He spends an hour out there. It breaks his heart when it’s crushed.”

He made a little dismissive noise. “Kids cry. They get over it.”

Then he turned and walked inside.

I stood there, fingers numb, heart pounding, and thought, Okay. That went well.

The next snowman died too.

Nick would come inside every time with a different mix of anger and sadness. Sometimes he cried. Sometimes he just stared out the window with his jaw clenched.

“Maybe build them closer to the house?” I suggested once.

He shook his head. “That’s my spot. He’s the one doing the wrong thing.”

My son wasn’t wrong.

I tried again with Mr. Streeter a week later. He’d just pulled in, the sky already dark.

“Hey,” I called, walking over. “You drove over his snowman again.”

“It’s dark,” he said without missing a beat. “I don’t see them.”

“That doesn’t change the fact that you’re driving on my lawn,” I said. “You’re not supposed to do that at all. Snowman or no snowman.”

He folded his arms. “You going to call the cops over a snowman?”

“I’m asking you to respect our property,” I said. “And my kid.”

He smirked. “Then tell him not to build things where they’ll get wrecked.”

I stood there shaking, running through all the things I wished I’d said.

That night, lying in bed next to my husband, Mark, I ranted in the dark.

“He’s such a jerk,” I whispered. “He’s doing it on purpose now. I can tell.”

Mark sighed. “I’ll talk to him if you want.”

“He doesn’t care,” I said. “I’ve tried being nice. I’ve tried explaining. He thinks an eight-year-old’s feelings don’t matter.”

Mark was quiet for a second.

“He’ll get his someday,” he said finally. “People like that always do.”

Turned out “someday” was sooner than either of us expected.

A few days later, Nick came in with snow in his hair, eyes shining but not from tears this time.

“Mom,” he said, dropping his boots in a heap. “It happened again.”

I braced. “Who’d he run over this time?”

“Winston,” he muttered. Then he squared his shoulders. “But it’s okay, Mom. You don’t have to talk to him anymore.”

That caught me. “What do you mean?”

He hesitated, then leaned closer like we were spies.

“I have a plan,” he whispered.

Instant nausea. “What kind of plan, sweetheart?”

He smiled. Not sneaky. Just sure.

“Nick,” I said carefully, “your plans can’t hurt anyone. And they can’t break anything on purpose. You know that, right?”

“I know,” he said quickly. “I’m not trying to hurt him. I just want him to stop.”

“What are you going to do?” I pressed.

He shook his head. “You’ll see. It’s not bad. I promise.”

I should’ve insisted. I know that.

But he was eight. And in my mind, “plan” meant maybe putting up a cardboard sign. Or writing “Stop” in the snow with his boots.

I did not imagine what he finally did.

The next afternoon, he rushed outside like always.

I watched from the living room as he headed straight to the edge of the lawn, near the fire hydrant. Our hydrant sits right where our grass meets the street, bright red, easy to see.

Usually.

Nick started packing snow around it.

He built that snowman big. Thick base, wide middle, round head. From the house, it just looked like he’d chosen a new spot closer to the road.

For the past five years, Jelly Roll, born Jason DeFord, has undertaken one of the most remarkable transformations in modern celebrity…

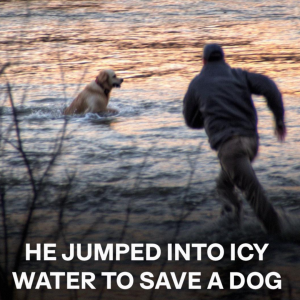

It was late afternoon, freezing, the kind of cold that slices through every layer. I was parked near the bridge,…

I’m 35, my son Nick is eight, and this winter our entire neighborhood learned a very loud lesson about boundaries.…

Melissa boarded the plane expecting an ordinary flight home, not a collision with her past. But when the pilot introduced…

I was halfway to my mother-in-law’s house with freshly baked lasagna when my lawyer’s frantic call changed everything. “Go back…

After years of waiting, Tony and June finally welcome their first child, but the delivery room erupts into chaos when…