From Early Struggles to Rock Stardom: How Childhood Pain Shaped a Legend

His mother, Constance Rose, was only 16 at the time, while his biological father was 20 — later described as…

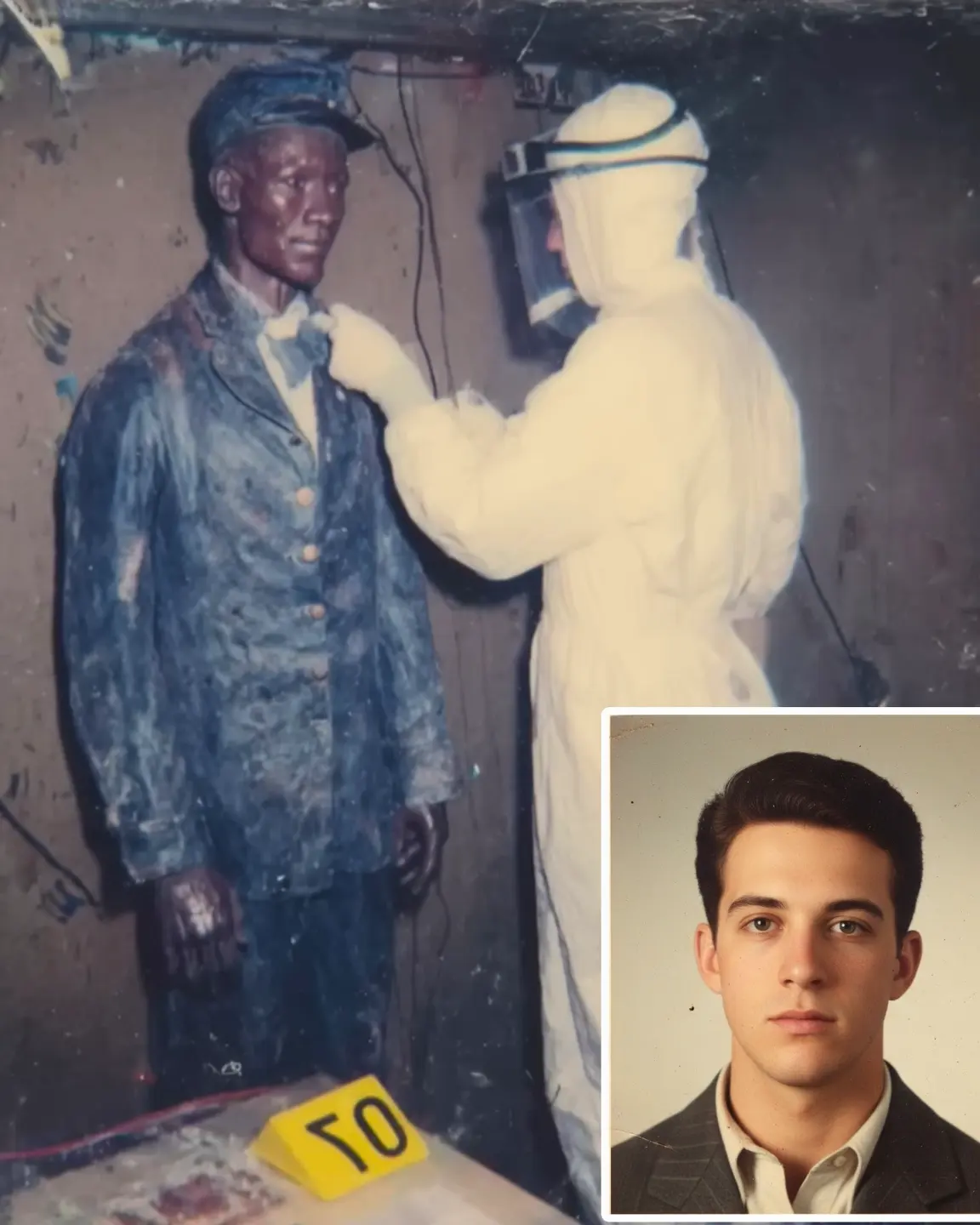

A museum kept a “wax figure” for 50 years — until in 2025, a new curator discovered it was actually a missing man.

“They believed him to be a wax figure for fifty years until a new curator found the truth that rocked a town.”

The first thing that caught Clara Whitman’s attention was the fragrance, which was subtle but off, like old varnish combined with an unidentified substance.

Clara had just been appointed curator of the Pine Bluff Historical Museum, a small-town institution in rural Missouri, when it came from the back room.

There was a sense of slowness throughout the museum, where each exhibit bore a ghost of the past, the floors moaned with untold stories.

With a clipboard in hand, she perused the exhibits on that June morning in 2025 as sunlight seeped through dusty windows.

She was getting ready for a makeover, which would include new labeling, lighting, and possibly even an electronic guide.

She was hired by the board because she was passionate about bringing forgotten history to life.

However, she could not have been prepared for what she was about to discover.

The Quiet Individual in the Corner

The museum’s beloved “wax figure,” a man sitting with a newspaper in his lap while wearing a brown suit and bowler hat, has been the focal point of the “Everyday Life in 1920” display for fifty years.

On field trips, kids posed next to him. Visitors made jokes about how “real” he appeared. He was lovingly referred to by the staff as Sam the Silent Man.

He had sat there longer than the majority of the employees had existed.

However, that odd odor drew Clara back as she moved around the room, clipboard pressed to her chest.

She knelt down to the figure and examined his hands, his shoes, and the way the light fell on his cheek. There was a problem. The skin had a leathery texture rather than a waxy one.

Over his hand, her fingers lingered. The half-moon ridges on the fingernails were too real. A shiver went through her arms.

Then she noticed it—a faint pattern that was still discernible despite the decades of dust—under a tiny tear close to the collar.

Human skin.

Her heart thumping, she took a step back.

The museum was completely silent for a few seconds. The air conditioner’s hum. The sound of a clock in the distance. Additionally, a man who wasn’t supposed to exist.

The Finding

Clara contacted maintenance, forcing herself to sound composed. Her voice was too bright as she continued, “I need this mannequin moved.” “With caution.”

A brittle fracture rang through the air as the workers came and removed him. One man almost dropped the figure and cursed.

“What was it?” he inquired.

Clara took a swallow. “Bone,” she murmured.

Yellow tape was used to close off the museum in a matter of hours. Reporters hovered near the doors as police flooded the scene, radios blazing.

By evening, it had been decided that the “wax figure” was actually not wax. Decades of dry air and shellac applied by well-meaning curators who wished to prevent their “exhibit” from breaking had preserved the mummified guy.

Like wildfire, the news spread throughout Pine Bluff.

No one had noticed the missing individual who had been silently sitting beneath glass in the museum for fifty years.

Arrival of Detective Mercer

That same evening, Detective Ryan Mercer showed up. He was a calm, methodical man in his mid-forties who exuded quiet authority.

Throughout his tenure, he had witnessed several cold cases, accidents, and drug busts. However, this? For fifty years, a corpse on exhibit as art? It resembled something from a Gothic book.

According to the autopsy, the individual passed away in the early 1970s. Not a trace of violence, but also no identity.

Late that evening, Clara sat in her office and gazed through the glass doors at the display. The impression that the man, whoever he was, had been waiting persisted.

The Association with Carnival

Mercer and Clara started looking through the museum’s records the next week. The majority of the acquisition records were half-faded, handwritten, and yellowed.

Then Clara noticed a solitary 1974 note that read, “Received donation from traveling carnival — Harlan’s Marvels,” written in blue ink.

Mercer was intrigued by that name.

A traveling sideshow, Harlan’s Marvels featured oddities, fortune tellers, and curiosities, much like the carnivals that toured the Midwest in the 1960s and 1970s.

One headline caught Mercer’s attention when searching through old newspaper clippings:

“Harlan’s Marvels Closes Amid Owner’s Unsolved Absence Mystery.”

In 1974, the year the museum acquired its enigmatic “wax figure,” the owner, Eddie Harlan, had disappeared.

A Horrifying Knowledge

Although former carnival employees were dispersed throughout several states, Mercer was able to locate one, Charlie Dunn, who is currently 83 years old and resides in Oklahoma.

“I recall that incident,” Charlie replied in an aged, gravelly voice on the phone. It was dubbed The Time Traveler. A actual embalmed man, supposedly, is evidence of time travel gone wrong. We all believed it to be a gag.

“Who knew where it originated?” Mercer inquired.

Eddie claimed to have purchased it at a mortuary auction, I believe. claimed it was a good deal. However, we sold everything for a low price once the carnival ended. I suppose your museum received it next.

As to the Pine Bluff Museum’s logbook, “The Time Traveler” was acquired for $30.

$30 for the body of a man.

The Face’s Hidden Name

A national database received the DNA from the body. Weeks went by. Outside the museum’s entrance, reporters set up camp. Every major outlet carried the story:

“After 50 years, a wax figure was discovered to be a real human body.”

“NOBODY KNEW THE SMALL TOWN’S MUSEUM HAD A MUMMY.”

The DNA results were finally returned.

The man was Arthur L. Maier, a Kansas City traveling salesman who vanished in 1973 while traveling to Tulsa. His body had never been found, but his automobile had been discovered abandoned at a gas station.

Susan Maier, his daughter, was now 64 and residing in Denver. She sobbed on the phone when the cops called her.

“I thought he left us all these years,” she said. My mother passed away believing he had fled.

Susan closed her mouth and let the tears fall down her cheeks when Clara showed her a picture of the museum’s “Sam the Silent Man.”

“That’s him,” she murmured quietly. “That’s my father.”

The Morality of Ignorance

According to the coroner, Arthur’s death was most likely caused by heat stroke or heart failure.

The tragedy was one of neglect, miscommunication, and the gradual degradation of human dignity rather than murder.

Arthur Maier had died alone, been sold, shown, stared at by hundreds, and thought to be a prop.

Speaking softly to a local reporter, Clara said:

“I’m not bothered by the terror. It’s the lack of interest. that no one noticed him for the fifty years he sat there.

A Funeral, Finally

Arthur’s remains were returned to his family by August. Under a brilliant blue sky, the funeral was held in Kansas City.

Beside the little headstone that said, “Arthur L. Maier — Finally Home,” was his daughter Susan.

Clara stood quietly in the back and attended as well.

She had just intended to restore an exhibit, but instead she had unearthed a tragedy: a guy who had been lost to time and had been accidentally recovered.

Susan gave her a hug after the service.

She declared, “My father can now rest.” “Because you took the time to look more closely.”

The Man Who Was Not Visible

The “Everyday Life in 1920” display had changed by the time the museum reopened six months later.

The wax figure had been replaced by a new exhibit called “The Man We Didn’t See.”

Arthur’s possessions were behind glass, including a bowler hat, a copy of his newspaper, and the faded picture of him grinning next to his 1972 sedan.

The text on the plaque said:

This man was solely known as Sam the Silent Man for half a century.

Arthur L. Maier was his name.

May we always remember the tales that are concealed from view.

People traveled from all around the nation. Some people left flowers. “Rest in peace, Arthur,” was one of the remarks left by others in the guestbook.

“At last, you were spotted.”

The Tale That Reverberated

The narrative persisted even after the media excitement subsided.

The case was utilized in museum ethics classes at universities. An essay titled “When History Forgets It’s Human” was published by the Smithsonian.

Then came documentaries. In one, Clara made an appearance while quietly discussing the teachings she had discovered.

She stated, “Museums are about memory.” However, occasionally we lose sight of the fact that the items we conserve were once owned by actual individuals. One of them was still in this instance.

What Arose Clara’s life changed after a few months.

She received invitations to give lectures on artifact provenance—the process of determining an object’s origin—all throughout the nation. To make sure that no history or individual would ever be mistaken again, she collaborated with other small museums.

Detective Mercer kept in touch and frequently spent peaceful mornings at the exhibit. At one point, he warned her, “You didn’t just find a body.” “You discovered a lesson.”

Clara gave a small smile. “No,” she replied. “He located us.”

A Community That Reminded

The Pine Bluff Museum’s attendance increased the next year. However, the tone was more significant than the figures. The hall was now filled with solemnity instead of laughter.

Now, visitors came to remember rather than merely to see.

Clara also strolled past the glass case in the silent building each morning before it opened.

The warmth of Arthur Maier’s effortless smile would be captured by the sunshine as it hit the picture.

For a brief instant, it seemed as though he was finally recognized—not as an object of interest or display, but as a man who had lived, loved, and was finally remembered.

The Guestbook as an Epilogue

Clara looked through the museum’s guestbook months later. Thousands of messages, hundreds of signatures.

But she was stopped by one page. A nice message in cursive said:

“I appreciate you locating my dad.

He had always had a passion for history.

He is now involved with it.

— Susan Maier.

Clara carefully closed the book.

The Missouri sky was glowing orange with sunset outside.

She believed that history is more than just the things we save. That’s what we see at last.

The man who had remained in quiet for fifty years had finally been seen at Pine Bluff; he was a human being who awaited remembrance, not a wax figure or a curiosity.

His mother, Constance Rose, was only 16 at the time, while his biological father was 20 — later described as…

Black sesame seeds, also known as Sesamum indicum, have been used for thousands of years in traditional medicine, cuisine, and…

THE MAN WHO LEFT, THE WOMAN WHO STAYED, AND THE LOVE THAT REFUSED TO DIE After nearly 47 years of…

From ancient riverbanks to modern dinner tables, fish has been one of humanity’s earliest and most important foods. Civilizations throughout…

Modern neuroscience has revealed something remarkable: the simple act of meditating for less than half an hour a day can…

My stepsister resented me and never missed a chance to mock my appearance or abilities. At my wedding, she tripped…