I Thought I’d Just Found the Love of My Life—Until a Single Object Revealed Who He Really Was

I thought I was building a future with my boyfriend until one forgotten object from my past made him freeze.…

Scientists Uncover the Cause Behind the Death of Billions of Sea Stars

For years, the ocean floor has been telling a quiet but devastating story.

Along coastlines once alive with color and movement, scientists began noticing something deeply wrong. Sea stars—icons of marine life, resilient survivors for hundreds of millions of years—were vanishing at an alarming rate. Some appeared twisted, others disintegrated into fragments, their arms detaching as if the animals were slowly unraveling from the inside.

What started as isolated observations soon became undeniable.

Billions of sea stars were dying.

The first large-scale reports emerged in the early 2010s. From the Pacific coast of North America to colder northern waters and even parts of the Atlantic, entire populations of sea stars collapsed within months. Tide pools that once held dozens of individuals were suddenly empty.

This was not a gradual decline.

It was a collapse.

Scientists referred to it as Sea Star Wasting Syndrome, a condition so aggressive that healthy sea stars could deteriorate within days. Arms twisted unnaturally. White lesions appeared. Tissue softened and broke apart. Eventually, the animals lost structural integrity entirely.

For creatures known for their toughness, the speed of destruction was shocking.

At first, researchers suspected a single pathogen—a virus or bacterium spreading rapidly through populations. A densovirus was identified in some cases, raising hope that the mystery had been solved.

But the evidence didn’t line up.

The virus appeared in both healthy and dying sea stars. Some affected areas showed no clear presence of the pathogen at all. Other regions with the virus showed no mass die-offs.

The pattern was inconsistent.

It became clear that this was not a simple outbreak caused by one microscopic villain. Something larger, more complex, was at play.

After years of experiments, field observations, and modeling, scientists reached a critical conclusion:

The mass death of sea stars is primarily driven by oxygen deprivation linked to climate change.

More specifically, warming ocean temperatures set off a chain reaction that ultimately suffocated sea stars at the microscopic level.

Sea stars do not breathe like fish. They rely on passive diffusion—oxygen moves directly from seawater into their tissues through their skin. This system works well in cool, oxygen-rich water.

But warm water changes everything.

As ocean temperatures rise, water holds less dissolved oxygen. At the same time, higher temperatures accelerate the growth of bacteria in the water and on the surface of sea stars.

These bacteria consume oxygen as they break down organic matter.

The result is a deadly imbalance.

Microbial activity skyrockets.

Oxygen levels drop.

Sea stars slowly suffocate—without any visible struggle.

This process is known as Boundary Layer Oxygen Diffusion Limitation, and it explains why sea stars seemed to melt away rather than show signs of trauma.

Not all marine animals were affected equally. Sea stars were hit hardest due to their unique biology.

They have:

No gills

No lungs

No active respiratory system

Their survival depends entirely on the surrounding water chemistry.

When oxygen levels drop even slightly at the microscopic layer around their bodies, tissues begin to fail. Cells die. Structural proteins weaken. The animal loses its ability to maintain form.

What looks like “wasting” is actually systemic tissue collapse.

The connection to climate change is impossible to ignore.

Marine heatwaves—extended periods of unusually warm ocean temperatures—have become more frequent and more intense over the last two decades. During these heatwaves, sea star deaths spike dramatically.

In areas where waters briefly cooled, some populations stabilized. Where warming persisted, extinction followed.

This was not a random disaster.

It was a warning signal.

Sea stars are not just beautiful creatures. They are keystone species—animals whose presence shapes entire ecosystems.

Many sea stars are top predators, controlling populations of mussels, sea urchins, and other invertebrates. Without them, these species multiply unchecked.

The result?

Mussel beds overtake rocky shores

Kelp forests collapse due to exploding urchin populations

Biodiversity plummets

In some regions, ecosystems shifted permanently within a few years of sea star disappearance.

One species fell—and entire underwater worlds changed with it.

Some sea star populations have shown small signs of recovery, but progress is uneven and fragile.

Sea stars reproduce slowly.

Larvae are sensitive to water conditions.

Juveniles are vulnerable to predators and disease.

And the underlying problem—warming oceans—has not gone away.

Scientists warn that without significant changes in global climate trends, recovery may be temporary or localized at best.

Understanding the cause of the sea star die-off changes how scientists approach marine conservation.

It shifts focus from chasing individual pathogens to addressing environmental conditions. It highlights the role of climate-driven microbial processes—something previously overlooked in many marine disease studies.

Most importantly, it shows that climate change doesn’t always kill loudly.

Sometimes, it kills quietly.

At the cellular level.

In ways that look like mystery until it’s almost too late.

Sea stars have survived five mass extinctions. They have existed longer than dinosaurs. Yet within a single human generation, billions were wiped out.

Not by fishing.

Not by pollution alone.

But by subtle shifts in temperature and oxygen balance.

This should unsettle us.

Because the same mechanisms threatening sea stars are already affecting other marine organisms—from corals to shellfish to plankton at the base of the food web.

Locally, yes.

Protecting marine habitats from additional stressors—pollution, runoff, overfishing—can help ecosystems remain resilient. Marine protected areas give surviving populations a chance to stabilize.

Globally, however, the solution is harder.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is no longer an abstract goal.

It is directly tied to whether ocean ecosystems can survive.

The fate of sea stars proves that the ocean responds quickly—and brutally—to climate imbalance.

The death of billions of sea stars is not just a marine tragedy. It is a message.

It tells us that even ancient, resilient life forms have limits.

It tells us that climate change operates in complex, invisible ways.

And it tells us that ecosystems can collapse faster than we expect.

Sea stars did not scream.

They did not fight back.

They simply disappeared.

Scientists continue to monitor surviving populations, study adaptive traits, and explore whether some sea stars may be more tolerant of warmer, low-oxygen conditions.

Hope exists—but it is cautious.

Because the lesson of the sea stars is clear:

Nature will not wait for us to catch up.

What happens beneath the waves today may determine the health of oceans for centuries to come.

And the quiet loss of billions of sea stars may be remembered as the moment humanity realized that climate change was no longer a distant threat—but an active force reshaping life on Earth, one species at a time.

I thought I was building a future with my boyfriend until one forgotten object from my past made him freeze.…

On her way to bury her son, Margaret hears a voice from the past echo through the plane’s speakers. What…

When my son rescued a shivering puppy, we never imagined it would spark a quiet war with our fussiest neighbor.…

I thought my big business trip to LA was going to be just another day until a mysterious request from…

Donald had to move in with his son Peter after his house burned. But he started to think he was…

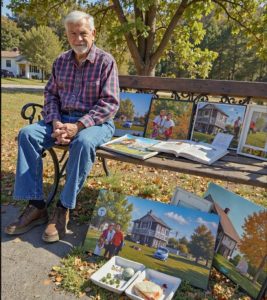

I was 70, painting to stay afloat, staying away from the usual hustle and bustle of the world, until one…